The concept of time capsules has long fascinated historians and futurists alike. These carefully curated collections of contemporary artifacts promise future generations a glimpse into our present moment. Yet when it comes to contemporary jewelry being preserved as archaeological artifacts, we encounter what scholars now call the Temporal Capsule Paradox - the inherent inaccuracy of present-day objects representing our era to future civilizations.

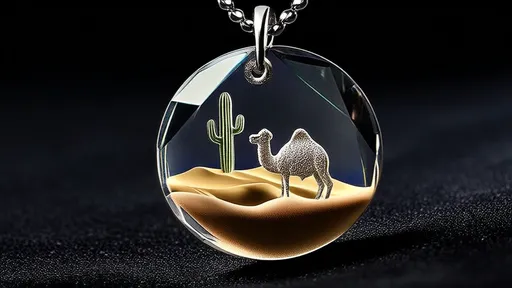

Modern jewelers consciously create pieces meant to withstand centuries, using durable materials and timeless designs. Paradoxically, this very durability and intentionality may distort future archaeological interpretations. The jewelry we deliberately preserve often represents elite tastes and aspirational aesthetics rather than the messy reality of daily adornment practices. A titanium and diamond ring preserved in an argon-filled museum case tells a radically different story than the faded plastic bangles actually worn by millions.

The materials revolution in jewelry design further complicates matters. Contemporary pieces increasingly incorporate advanced alloys, lab-grown gemstones, and smart technology components. While scientifically fascinating, these materials create an archaeological funhouse mirror effect. Future researchers might interpret our era as dominated by space-age minimalist designs, when in reality the best-selling jewelry items remain traditional gold pieces and costume jewelry.

Digital jewelry presents perhaps the greatest interpretive challenge. How will future archaeologists understand RFID-embedded rings or necklaces containing encrypted digital memories when the supporting technology becomes obsolete? The physical components may survive, but their cultural context and functionality could become as mysterious as Neolithic clay figurines. We risk creating what anthropologist Dr. Elena Petrov calls "the digital terra incognita" - physical objects pointing to digital realms that future scholars cannot access.

Contemporary jewelry preservation efforts often focus on designer pieces and luxury items, creating what future researchers might mistake as representative of our entire material culture. The everyday jewelry worn by most people - mass-produced, trend-driven, and often made of perishable materials - rarely survives in archaeological contexts. This preservation bias could lead to significant misinterpretations, much like Victorian archaeologists assuming all ancient Greeks wore marble-carved clothing based on surviving sculptures.

The paradox extends to jewelry's social meanings. Current preservation methods capture objects but often fail to document their complex cultural contexts - the Instagram posts showing layering techniques, the TikTok videos explaining sentimental values, or the online debates about cultural appropriation in design. Without these digital footprints, future scholars might interpret symbolic meanings completely differently than intended. A charm bracelet preserving locks of hair might be misread as religious relic rather than a memorial practice.

Perhaps most ironically, contemporary jewelry's future archaeological record may be most accurately preserved through accidental means rather than deliberate time capsules. The jewelry lost in drains, discarded in landfills, or left in forgotten storage units - subjected to natural degradation processes - will likely provide future researchers with a more authentic understanding of our material culture than the pristine pieces we carefully select for preservation.

As we continue creating jewelry for both present enjoyment and future discovery, we must acknowledge the inherent limitations of temporal communication through objects. The very act of selecting what to preserve introduces biases that future civilizations may not recognize. In trying so carefully to speak to the future through our jewelry, we may end up telling a story quite different from our lived reality - the fundamental paradox at the heart of all time capsules.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025